My aunt Goldie used to subscribe to the Reader’s Digest and I would look forward to reading it when we visited her house. I didn’t do more than glance at most of the articles, concentrating on just a few of the regular features. Every now and then, particularly in the early fifties, there would be a story about a heroic submariner or a remarkable explorer or a Jackie Robinson, but I mostly looked for “Laughter is the best medicine” and “The most unforgettable character I ever met.” Were I to contribute to Reader’s Digest W. Montague Cobb would be one of those most unforgettable characters in my life.

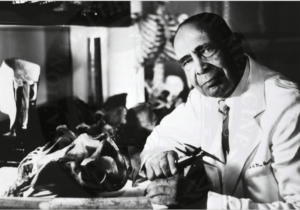

Dr. Cobb was the chairman of the anatomy department in the School of Medicine of Howard University when I was a medical student. There have only been a few people in my life that unequivocally deserved the appellation “intellectual.” Dr. Cobb was one of those. A renowned anatomist and anthropologist, calipers and skulls decorated his office. He contributed to the literature of medicine and edited a medical journal. But he was also a poet and a musician, a grammarian and a linguist, a political activist and a civil rights leader. He knew ancient history and modern history and art history. One of the first African-Americans to be admitted to Amherst, it was said that he graduated first in his class. Was that a Bach violin Partita that he once played in the cadaver room as most of my fellow students stared at him in disbelief and I stood transfixed with surprise and pleasure and joy and envy? I can still hear him reciting Tennyson’s Ulysses, on a rainy, dark October day as we searched for the sural nerve, his booming voice periodically punctuated by Indian Summer claps of lightning. His rumbling, full baritone exhorted us to “smite the sounding furrow.” and “sail beyond the setting sun.” Ulysses instantly and forever became the poem I love reading aloud more than any other and, no doubt as a result of his introducing me to the great poet, I have been collecting nineteenth century editions of Tennyson for many years. A few weeks ago I happened to read Ulysses again and was struck by the intensity of its meaning for the recent years of my life, as I look nervously at my own lengthening shadows. I find myself still striving very hard to keep sailing beyond that setting sun.

How, you might ask, did an exceedingly provincial, white, Jewish boy from Brooklyn end up as a medical student at Howard University, an institution founded to provide outstanding higher education particularly for African-Americans, but also an institution in no way sectarian?

More about that at some later time.

It has been my privilege to be allowed to learn from outstanding and knowledgeable teachers; William Montague Cobb was one of the best. I was his student in the first year anatomy course in September 1960, less than a decade after ‘Brown v Board of Education.’ He was an innovator, whose creativity was ignited by a desire to guarantee that his students learned well and by a special determination that the young black medical students he helped mold compare in knowledge to any students anywhere. His passion for life and for knowledge and for excellence were an inspiration from the first day he taught me and my class and he is always first on the list when I count the teachers who have most affected my life and have most contributed to my career as a physician and a pathologist, and also as a person. I can now clearly recognize that his approach to education, despite the massive amount of material there is to learn in a classic anatomy course, was in keeping with the philosophy of Yeats: “Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire.”

Some of my classmates hated anatomy with unbridled passion and hated Cobb even more. The thought him pompous, I thought him grand. They thought him patronizing, I thought him witty. They thought him too tough, I thought him inspirational. He definitely lit the fire of learning for me. Five years after my class graduated he was forced to resign as head of the department, swept away by the anger and militancy inflaming his students, and all students, during those last few turmoil driven years of the nineteen-sixties. My life was busy at that time and I never learned the complete tale of those events. Perhaps I didn’t want to know about them.

Cobb really could be as pompous as any potentate, arrogant and supercilious, as he walked through the laboratory testing our ability to identify this muscle or that bone, his mocking criticisms razor sharp if he thought you were lazy or indifferent. When he called you “doctor” the contempt dripped from his tongue onto the floor, seemingly splashing all over your shoes. But if you were genuinely confused or, as was true for some of my classmates, hopelessly inept in mastering the wealth and the burden of all the details of anatomy, he was gentle and encouraging, offering unique clues, not present in any textbook, that might help you remember some anatomic landmark.

He demanded that we learn, no matter what. “It is better to have learned and lost, young doctors, than never to have learned at all,” he would proclaim, and at least one student believed him with all his heart and soul; I learned how to study, for the first time in my life, in Dr. Cobb’s class. He ignited in me the love of anatomy and the love of medical history.

Cobb was the editor-in-chief of the Journal of the National Medical Association, the JNMA, formed to provide a venue for scientific articles emanating from those hospitals of the United States predominantly staffed by African-Americans, at a time when the well-established and far better known, widely read JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association, may have been less hospitable to contributions from those physicians and scientists. He would encourage his students to submit papers to him for consideration.

During my sophomore year I had the opportunity to study a patient who had a rare type of lung cancer that was behaving in a distinctly uncommon manner. This tumor produced adrenocorticotrophic hormone, or ACTH, the hormone usually produced by the pituitary gland that stimulates the cortex, or outer portion, of the adrenal gland to itself produce hormones, the so-called adrenocorticoids. Adrenocorticoids are the type of steroids we hear about when they are inappropriately used by athletes, the type of steroids that sometimes get squirted into a troublesome knee joint or shoulder.

I was assigned to the patient, Mr. Harrison, or perhaps he was assigned to me, during the course in physical diagnosis, which was the first time we had the opportunity to work directly with patients.

When the pituitary produces ACTH in the usual manner it is regulated by the activity of the adrenal gland. When the steroids produced by the adrenal gland are, for a variety of reasons, secreted in amounts greater than normal, the constellation of signs and symptoms knows as Cushing syndrome develops. Sometimes this happens because of excess production from the adrenal itself and sometimes because of excess production of ACTH by the pituitary with secondary over-activity of the adrenal cortex. In the normal patient, high levels of steroids in the circulation lead to a “feedback” mechanism causing the pituitary to stop secreting ACTH, thereby stopping, at least temporarily, the activity of the adrenal cortex itself. When tumors, whether in the pituitary or elsewhere, produce ACTH they do so autonomously and do not respond to the levels of steroids in the blood, leading to Cushing syndrome, so-called because of a 1932 report by the pioneering neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing in which the typical patients were described.

As a part of the report on the patient that I was required to prepare, I reviewed the literature about Cushing syndrome associated with production of ACTH by a tumor, and read Cushing’s original report. In Cushing’s report the syndrome is due to excess production of ACTH by a pituitary tumor. In common usage, Cushing syndrome is generally thought of as being either of pituitary or adrenal origin, since the adrenal itself can be hyper-reactive or have a tumor secreting adenocorticoids. In my research I was able to find a report of a similar patient, written by a Canadian physician, W. Hurst Brown, published four years before the Cushing report. Indeed, Brown had described well what we now call Cushing syndrome but, in Brown’s patient, as in mine, the source of the excess ACTH production was not a pituitary tumor, but a lung tumor contributing to “ectopic” ACTH production.

My faculty supervisor recommended that I show the report I had prepared to Dr. Cobb for possible publication. This was a wonderful opportunity for me, leading to the first publication of an article I had written. Equally importantly, I had the opportunity to spend many hours with Dr. Cobb, in his decidedly cluttered office, struggling to transform my crude manuscript into something worth publishing.

Years later, after reading an article in a leading medical journal about Cushing syndrome, I wrote a letter to the editor of that journal commenting on the fact that Brown had really described the typical patient before Cushing. The letter was published and a gracious note from Brown’s widow, who still lived in Toronto, rewarded my effort.

W. Montague Cobb’s office was indeed a place of wonderment. Cobb had a great interest in the anatomy of the skeletal system, especially skulls, which irregularly adorned his worktable between the many medical books and journals, article reprints, and notepads, as well as the stacks of magazines. Time and Newsweek, newspapers, the Washington Post, the New York Times, history books, poetry books; even his violin fought for a precious few inches of that desktop. There were pictures of many of his teachers on the wall, as well as anatomic drawings.

Dr. Cobb’s technique of teaching, his “method of anatomy,” required that we draw whatever we were learning. He didn’t require that we challenge da Vinci, but did expect us to be able to show where muscles began and where they ended and to, at least, strongly resemble the original. He taught us to use drawing paper divided into blocks and to draw in sections, rather than attempting to draw a complex structure whole. He also taught us that it was best to listen to a lecture and not feel compelled to take notes. “Learn by first intention,” he would regularly proclaim. I have not taken detailed lecture notes since that time.

A half-century before any even imagined video recorders he prepared 8-mm movies for each portion of the body we would study, showing us the method of dissection and each of the structures we should be seeing. Dr. Cobb was the narrator and sometimes the filmed dissector. In our modern and fantastic world of computer-generated and modified films, his were distinctly primitive. But for us, at that time, they were a wondrous introduction to the complexities of human anatomy, preparing our minds for the tasks ahead in the cadaver room.

For our first examination we were required to draw the human skeleton, in scale, on a 11 x 14” piece of paper. We had learned how to do this only after he taught us the standards of drawing used by the great artists. The manual he gave to us had three sections; the middle devoted to the ways in which the great artists rendered human anatomy. daVinci did it according to one standard and Michelangelo another. Our standard was the seven and half heads scale for drawing the human body devised by Albrecht Dürer whose flowering as an artist began at about the time that Columbus left Lisbon.

Later examinations required that we be able to draw the muscles of the upper extremity or the back or the pelvis or the anatomy of the liver and bile ducts.

When it came time to learn the muscles, Dr. Cobb told us to go to the zoo, to go to see the bears. He wanted us to just sit and observe and come to appreciate how the flexors and extensors worked, and then to come back and study the comparable human muscles. “Just look at those bears and how they use their mighty muscles,” he intoned.

My classmates all, including me, were quite skeptical. One of them hesitantly raised his hand. “Dr. Cobb, those bears have a lot of hair on them, don’t they? How are we going to see their muscles?” A few muffled guffaws and giggles followed. But he just slowly looked around the room, peered, or so I thought, into each of our eyes. “Doubting Thomases, are we? Do you think I would tell you to study the bears if I didn’t believe it was useful? Tell me, doctors, why would I do that?”

I lived in a rooming house on Park Place, not too far from the Washington Zoo. One cold and damp November Sunday, the weekend before the examination on the muscles, I woke determined to discover whatever the bears had to offer. After a breakfast I now ruefully remember as almost certainly being scrambled eggs and bacon and hash brown potatoes and buttered toast, at the little corner restaurant on Columbia Road, I headed for the zoo. It started to drizzle and I put up my umbrella, my then quite ample belly more than full, and headed through the rain, clutching my briefcase close to my chest to keep it dry, wondering if I should better use my time just studying in my warm and cozy room, with the local classical music station, WGMS, in the background.

The period of zoo modernization had not yet occurred and there was nothing sparkling or exciting about the Washington Zoo. In those years it was old and tired. Although clean and well maintained, it was much in need of the new methods of keeping animals in captivity that wouldn’t become the style for another ten to fifteen years.

The zoo was completely empty that day. I didn’t see another human being at any time during the more than two hours I was there.

The rain and chill made it uncomfortable to even consider standing outside and it was obvious that the animals were all smart enough to get out of the now torrential downpour.

The bear house was in an old building, with cages surrounding a central visitor area. Although quite dry it was even chillier inside than it had been outside. A single hard wood, well-worn bench, marked here and there with carved initials and hearts and arrows, was in the center of the room and I sat there expectantly. The empty attendant’s office was in one corner of the room, just within the entry door.

The bears were fast asleep. The creatures were decidedly not stirring.

I sat there, in the stillness, for about a half-hour, listening to the staccato of the increasingly heavy downpour on the roof. I pulled out my notebook and looked over material I had read previously, but I really wasn’t interested in studying whatever was there. I paced slowly back and forth in front of the various cages. Some of the bears opened one or both eyes, generally only halfway, as I walked by, but none of them moved to get up, to start their usual nervous pacing back and forth. There were no rippling muscles, no mighty roars. I buttoned my raincoat and picked up my umbrella, heading for the big cat house. Dr. Cobb had specifically recommended the bears, but I hadn’t gotten anywhere with them and thought I could still get some value from the cats. It seemed to me that you could really see muscles on the big cats, and I have always loved tigers.

The cats were also asleep.

Tigers, panthers, leopards, jaguars. Lions.

All asleep in their respective cages.

The building was dimly lit and, with the dark skies outside, almost dark. The attendant’s office, immediately inside the entrance door as in the bear house, had the only bright light, the bulb of the incandescent lamp on the desk throwing a brief shadow to my left as I walked by. I quietly closed the umbrella and took off my raincoat and sat on the cold, gray marble bench in the center of a cold, gray marble room. I took my glasses off and wiped them free of drying raindrops. I peered into the quiet cages.

If I can’t see muscles in motion, I suppose I might as well study, I thought, pulling the big red Gray’s Anatomy textbook from my briefcase. I thumbed through the first section on the skeleton, which was well underlined with many notes in the margin, and turned to the muscles of the back. The dull-red coloration of the lattisimus dorsi, the obliques or the trapezius did nothing to capture my attention and the words and lines soon started lazily swimming together. Some of the cats were actually snoring, and that low, guttural rumble was, at the very least, calming, almost hypnotic. I found myself struggling to keep my eyelids open but knew they were slipping lower and lower despite my spasmodic efforts to snap them wide. The yellow light spilling onto the tile floor from the attendant’s office was just at the very edge of my field of vision and I was almost as relaxed as the cats, ready to join them in slumber.

I shook my head to keep awake and reminded myself that I needed to study the muscles today, and not enjoy the glorious pleasures of a mid-day, rainy day nap.

I need to learn about muscles! This just is not working, Dr. Cobb.

Despite my best intentions the surroundings conspired successfully against me. The powerful storm had lessened and there was a soothing pit-pat, pit-pat of rain on the skylight above me. This steady, soft drumbeat, the gray light, the rhythmic snores, the quiet, the solitude, all lulled me into the all too welcoming arms of Morpheus.

I don’t know how much time went by. I know it could not have been more than a few minutes, I suspect it was only seconds that I dozed.

Without warning the delicious reverie was abruptly and violently interrupted by the piercing ring of the telephone in the attendant’s office. I literally jumped from the bench, my feet momentarily leaving the cold, dirty stone floor, the surprise of the sound causing me to contract my own somewhat modest muscles enough to accomplish that remarkable feat.

“Good grief!” I said, hoarsely and tremulously, ready for an overwhelming cacophony of ferocious jungle roars.

I looked all around.

Not a single cat had moved.

Not an ear had wiggled.

Not a single furred eyelid had crept up to expose even one blood-shot feral eye.

Not one moist nostril had dilated.

Not a bristly, setaceous whisker had twitched.

The goosebumps on my arm felt mountain top-high and perhaps were even quivering as I sat down and again looked all around, this time moving myself slowly around the smooth marble bench surface to slowly and methodically face each of the cages and try to understand what awful process had allowed these magnificent creatures, once of the jungle, to be able to ignore the shrill ring of a telephone as it tore through the absolute noiselessness. I might just as well have been surrounded by middle-aged, suburban husbands asleep on the couch with a dull and ponderous football game unwatched before them, disorganized mounds of half-empty beer cans at their feet.

I did not go back to that zoo for three years. During my last few months in medical school my wife and I wheeled our infant son along the zoo paths on a bright, sunny end-of-April day. We introduced him to the original Smoky Bear, rescued from a New Mexico forest fire and brought to Washington for his remaining twenty-six years.

We taught our son how to drink from a straw on that day and he almost said “bird.”

On this glorious spring day the big cats were all in the outside cages. The tigers paced back and forth, muscles clearly rippling as they measured and remeasured the meager boundaries of their contained existence, and, as I recalled that day when I had come to study anatomy and found great jungle creatures deaf to the piercing sound of the telephone, the despondency I had felt before returned in full force.

I have never really enjoyed a zoo since that day. They still make me unhappy, dispirited, even the modern ones with ample open space for the animals to roam and run. The bars are unseen, but I can’t forget that they are still there somewhere.

September 16, 2014 at 6:40 pm

Just the mere mention of Aunt Goldie brings a smile to my new LPT face!

She and your Mother were my two favorite Geller Aunts.

PS

I loved your piece on Med School and your mentors.

February 23, 2015 at 5:53 pm

Bobby,

Thanks for the wonderful comments to the blog posts. You probably have at least as many stories as I do – maybe you should develop your own blog. I had completely forgotten that basement until you reminded me about the CSA – and then I could almost visualize it.

How about lunch some day in April?

Best to you and Nadia.

September 19, 2014 at 3:52 pm

I enjoy your way with the written word l’il cousin. How about a treatise on Grandpa’s basement and the wonderments therein. Swords, muskets, Confederate garb and my favorite a big holster with CSA on it. Don’t forget the coal in the coal bin, my mother never did! I have a feeling you might have had a dusting or two at one time or another yourself.